Spanish and Portuguese Rivers

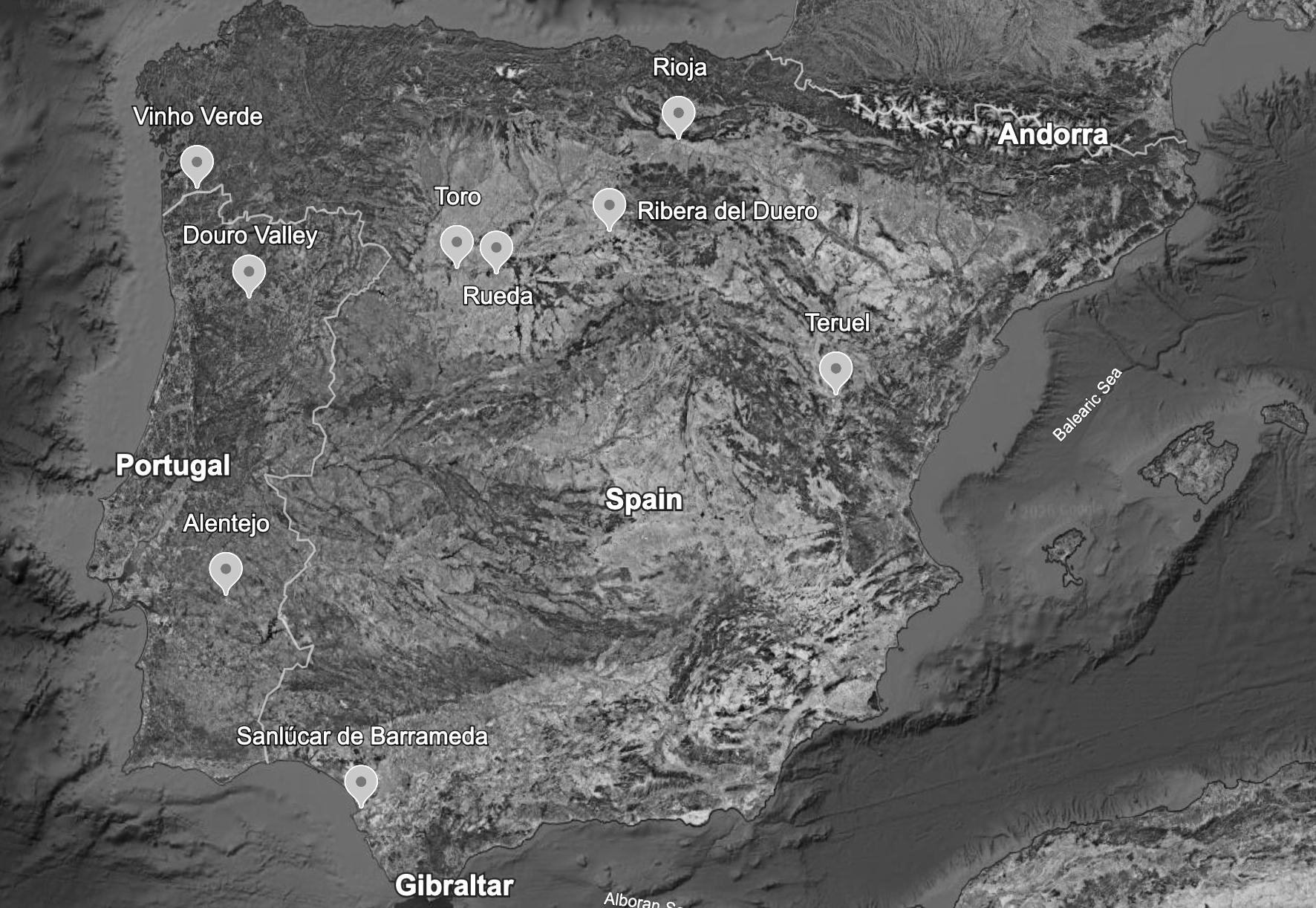

Spain and Portugal, on the Iberian peninsula, share several rivers which flow from Spain into the Atlantic Ocean. In wine terms, there are three which are extremely important: the Duero which becomes the Douro in Portugal; Minho (Miño in Spanish) which is the border between northern Portugal and Galicia; and Tejo (Tajo in Spanish, Tagus in English), which ends in Lisbon. There are also a couple of important wine rivers solely within Spain: the Ebro begins in the Cantabrian mountains near the Atlantic and ends in the Mediterranean in Catalunya; Guadalquivir, Spain’s only navigable river, starts south-east of Madrid and continues through Sevilla and finishes in the confluence between the Atlantic and the Meditteranean.

All of them are connected to major wine regions: the Ebro most notably with Rioja; Guadalquivir with Sherry; Deuro with Ribera del Duero, Rueda, and Toro; Douro with Port; Tejo with Alentejo and other areas around Lisbon; Minho with both Vinho Verde and Rías Baixas. In the varied climates of Spain and Portugal, these rivers play a significant role.

Minho

The river Minho is, on sight, not the most impressive river. At its widest it’s just 2km, but its 340km length is significant because it forms the northern border between Portugal and Spain. It’s an eerie experience standing by the river, as one can see the other country almost a stone’s throw away. Yet the river divides two connected but very different cultures. Crossing the river by car from Spain to Portugal, which takes about ten seconds, everything changes: the language, the name of the river, the car number plates, the time zone. The vine training system changes too. In Rías Baixas, which is more strongly affected by the Atlantic, the pergola system is used to allow air circulation. The two highest quality villages in Vinho Verde, Monçâo and Melgaço, are on the banks of the river and VSP is used. The grape remains the same, with a different spelling: Albariño becomes Alvarinho. But the style subtly changes, as malolactic fermentation is encouraged in Rías Baixas but not Vinho Verde. The cultural differences that Minho causes is reflected in the wines.

Douro/Duero

The river, nearly 900km long, is associated with some of the most prestigious and important wine regions in both Spain and Portugal. One of the regions it’s not connected to is Rioja, but it starts just south of it in the province of Soria. The first wine region directly connected to the river is Ribera del Duero. Although not that far from Rioja, Ribera del Duero has a very different climate, hot and dry. The quality of the wines comes from the high elevation plantings on the slopes that rise up above the river, up to 850m. This is similarly the case in both Rueda, where the production of quality white wine would not be possible without elevation above the river, and in Toro, a wild, remote region where plantings are up to 750m. This is the epitome of continental Spain, mountains rising above the river.

Duero flows into Portugal, where it becomes the Douro. At first it’s flat and very hot, but the river falls into the heart of the Douro valley where dramatic slopes rise up: this is one of the most beautiful wine regions in the world. This used to be such a remote region that until the 1970s wines could only be transported by boat to Porto by the Atlantic Ocean and there was no electricity until the 1980s. The slopes are steep, protected from erosion by terraces, looming high above the river. Once the Douro passes through the mountains, it reaches Porto and its sister city Vila Nova de Gaia, flowing out into the Atlantic Ocean. Porto is the wettest major city in Europe; the wines of the Douro were transported by the river to age in the much cooler, more humid conditions than hot, dry, remote Douro valley.

Tejo

The river Tejo is the longest on the Iberian peninsula, stretching just over 1,000km (roughly the same as the Loire) from Sierra de Albarracín in Spain into the Lisbon estuary. Water is at the heart of Lisbon’s history and culture, the starting point for boats sailing to South America and also part of the city’s beauty with its hills rising above the estuary.

The river starts in central eastern Spain in the province of Teruel, high in the mountains at nearly 1,600m elevation. It passes south of Madrid through Toledo, an historic, small city where wine is made in the foothills of the mountains. It continues its journey through Extramadura, a hot region where a little wine is made, including Cava, but more known for its acorn-fed pigs. It then goes into Portugal, the high-volume wine region of Estremadura, through the Roman town of Evora, and then onwards into Lisbon.

There are two wine regions in Portugal named after the river: Alentejo and Tejo (formerly Ribatejo). Alentejo, where Evora is the main town, is rural, its economy based around farming and it’s where the majority of cork trees are found. The river provides irrigation as this is a dry climate. Traditionally, Alentejo was a poor region, especially under the facist dictatorship, and the wines lacked any quality but there has been significant investment and there are many interesting wines being made.

The Tejo region, as the name suggests, is defined by the river which splits styles of wine and production in two. To the north of the river, there are smaller growers and producers while to the south of the river production is high volume. The soils on either side of the river are fertile and alluvial, directly formed by the proximity to the water. As a result, yields are high: Tejo is one of the highest-volume regions in Portugal but also one of the wealthiest rural regions in the country.

Ebro

The 930km river Ebro starts in the Cantabrian mountains, which, coincidentally, is where Rioja begins. It flows through the centre of the valley, with high mountains rising above it. In Rioja Alavesa and Rioja Alta, the valley is quite narrow and plantings are higher up. As the river grows, the valley broadens and the soils become fertile and alluvial; arguably the best wines are made from higher elevation away from the river. It then pushes downwards into Rioja Oriental (aka Baja), the warmest and lowest sub-region of Rioja, flowing into Navarra and then Catalunya. Within Rioja, there are several small valleys sequestered in gaps between the mountains which have been formed by tributaries of Ebro, such as Oja (where the region’s name comes from) and Najerilla. While Ebro forms the basis of Rioja’s geography, these tributaries add to the diversity of the styles of wine. It’s often been too easy to generalise about Rioja just being one place, but the many rivers and the valleys they help form show it is a much more varied region.

Guadliquivir

The river Guadliquivir originates in the Sierra de Cazorla mountains near Jaén, travelling westwards to Córdoba and then Sevilla, moving southwards to end in the Bay of Cádiz. In the hot, dry climate, it’s an important source of water for farming. Perhaps where Guadliquivir becomes most important for wine is in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, the small coastal town where the river ends and where Manzanilla is made. The wines are stored in bodegas right next to the river, which creates cool, humid conditions which are perfect for the formation of flor. Manzanilla is a more delicate version of a Fino, and the river is a large reason for the subtly different style. And, of course, the historic success of Sherry and the development of its fortified wines is because of the region’s proximity to water which allowed the wines to be traded.

Water is all important in many of Spain and Portugal’s regions, which can be hot and arid. The existence of these rivers is why communities exist—and why wine can be made.