The Mediterranean

The Mediterranean is the great sea of southern Europe and northern Africa, its name evoking images of pristine blue sea, glorious beaches, tourists from northern Europe sunbathing—and of wine. From Andalucia to Alicante to Valencia to Catalunya to Roussillon and Languedoc to the southern Rhône and Provence, as well as the Balearic islands, Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily, the Mediterranean influences many wine regions for various styles of wine. Such is its importance, it gives its name to a “Mediterranean climate,” ideal for wine around the world in California, Chile, South Africa, and Australia.

The summer months are warm and dry, perfect growing conditions. Rain falls during the winter, which provides water for the growing season in the summer. The sea also provides a cooling influence, channelling breezes and winds inland. There’s no problem getting the grapes ripe, but the Mediterranean helps provide balance and freshness.

It’s not always ideal, as temperatures in the Mediterranean can get hot. Algarve in southern Portugal is a major tourist destination but it’s not known for its wines. Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia are on the edge of being able to successfully grow grapes, although the low amount of production in those countries is as much due to religious and political reasons as to the climate.

The city of Cádiz is a port on the Mediterranean, where Christopher Columbus sailed to the Americas and which the street plan of Havana in Cuba is modelled on. In 1587, Francis Drake raided Cádiz and took 2m litres of Andalucian wine with him back to England. He declared it the patriotic duty of every Englishman to drink Andalucian wine to show the superiority of England over all other European countries. Sherry—an Anglicisation of the city of Jérez, which is slightly further inland—was born. As the wines became popular, they had to be fortified to survive the journey from the Mediterranean to England.

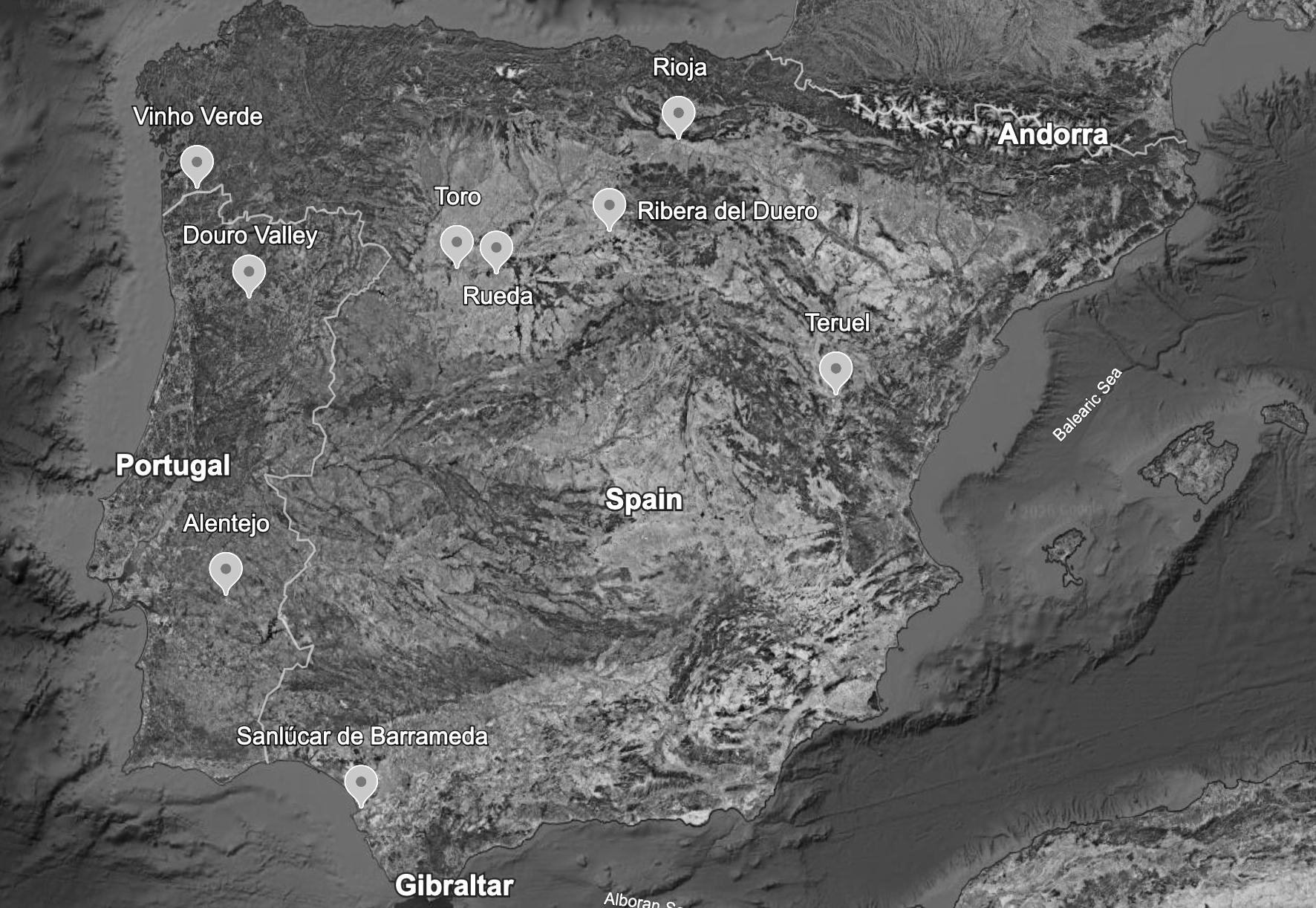

The Sherry region is conditioned by two major bodies of water: the Guadalquivir river, which is 650km in length, flowing through Cordóba and Sevilla into Cádiz which is where the Mediterranean meets the Atlantic Ocean. The river and the sea create humid conditions vital to the production of fino and manzanilla. The humidity in the cellar is one of the integral causes of the formation of flor, whose nature changes according to the town or even the position in the cellar. Sanlúcar de Barrameda is a small town next to both the river and the sea: there is a particular saline quality to the manzanilla made there, while a fino from Jérez is a little bit richer and fuller. The proximity to the Mediterranean is central to Sherry’s identity; further inland, away from the sea, Montilla-Moriles is a region which also makes Sherry-like wines. It’s around the city of Cordóba and is one of the hottest regions in Europe: a fino from Montilla-Moriles is distinctly different than Jérez.

Moving along the Mediterranean Spanish coast to Málaga, where the series of seaside resorts begins. There’s also historic sweet fortified wine made around Malaga, but in general it’s too hot for table wine. The coast then travels up to Alicante and then Valencia. These two cities/regions also get hot, for full-bodied, ripe red wines, although inland at high elevation (Jumilla is over 700m) cool air from the Mediterranean allows good quality wine to be made. This is typical of Spain’s Mediterranean coast: warm and sunny by the sea, quickly rising into much cooler, arid mountains.

Further north in Catalunya, it’s a similar story although not as hot as Valencia or Alicante. Vineyards, especially for Cava, are planted right by the coast. It’s still easy to get the grapes ripe, but there are plenty of localised growing conditions. There are vines grown at sea level, in the valley between the coastal and inland mountains where cool air from the sea is trapped, and at high elevation above the valley. After the mountains, the plateau begins, almost desert like: the arid town of Lleida is completely different from the seaside resort of Sitges just 140km away.

The Mediterranean culture is not connected to one nation; instead, it’s shared through trade, travel, and family. When I visited Roussillon in southern France just before the pandemic, I tasted with a producer, Georges Puig, in a tiny, old village. He has traced his family’s history in the village to the 1200s, which may seem quite static. But he has winemaking family relatives in Mallorca, Barcelona, and Valencia. His wines are French, Catalan, but most of all Mediterranean—especially the fortified wines made all along the French and Spanish coasts.

The south of France has always looked towards the Mediterranean rather than towards Paris. Languedoc, further along the coast, derives its name from the Occitan language where the word for yes is oc rather than oui. In wine terms, it remains defiant and anarchic, reflecting the wild remoteness of the Mediterranean where disparate communities are connected to each other.

That’s seen on the islands: the Balearic islands became refuges for artists and those wishing to escape modern life; the savage nature of Corisca; the rocky wilderness of Sardinia; the mafiosi and volcanoes of Sicily; the ancient history of the Aegean islands in Greece; tiny islands across the Mediterranean which still somehow produce wine commercially. All of these islands traded with each other, and with large European countries, the sea a passage between them all.

Provence is a famous, much-visited region but until the late nineteenth century it was remote and little known. St-Tropez, now a town overrun with the filthy rich, was only accessible by boat. Artists and writers moved to Provence attracted by its rural remoteness. Slowly, its wines became known and influential: the bulky Mourvèdre from the terraces overlooking the sea in Bandol; the pale rosés drunk by tourists and imitated by winemakers across the world; also herbal-based products such as soap and liqueurs.

The Mediterrean also touches Israel and Lebanon, looking towards both Europe and Asia. It’s the boundary between Europe and Africa. There are many languages spoken, and many dialects of those languages. It’s been the site of conflicts, of regional invasions, of national collaborations, of division. But it’s always been the Mediterranean, wine made there for millennia.